Shea becomes the go-between to introduce us to a new world- or rather, an old world. A world full of culture, history, movement and memories, which is on the verge of being lost.

Shea wishes to ‘bear witness’ to life in the Arctic and to allow all us ‘southerners’ to experience the harsh beauty of life there. He acknowledges though that a new Arctic is emerging and its peoples are torn between adapting to the emerging new world and looking back to preserve and hold tight to the traditions of the past. From Ellesmere Island to the Northwest Territories to Alaska, Norway and Grøenland (Greenland), Shea takes the reader on a deeply personal journey, exploring the liminal spaces and thresholds which exist in the various Arctics. Through the eyes of those not living in the Arctic, there is only one Arctic, but for its peoples, the landscape is charged with different tribes, languages and histories. ‘Four million people living in the region. Some four-hundred thousand of them are Indigenous. Dozens of languages, dozens of tribes and nations and homelands, all of them scattered across just eight modern states.’

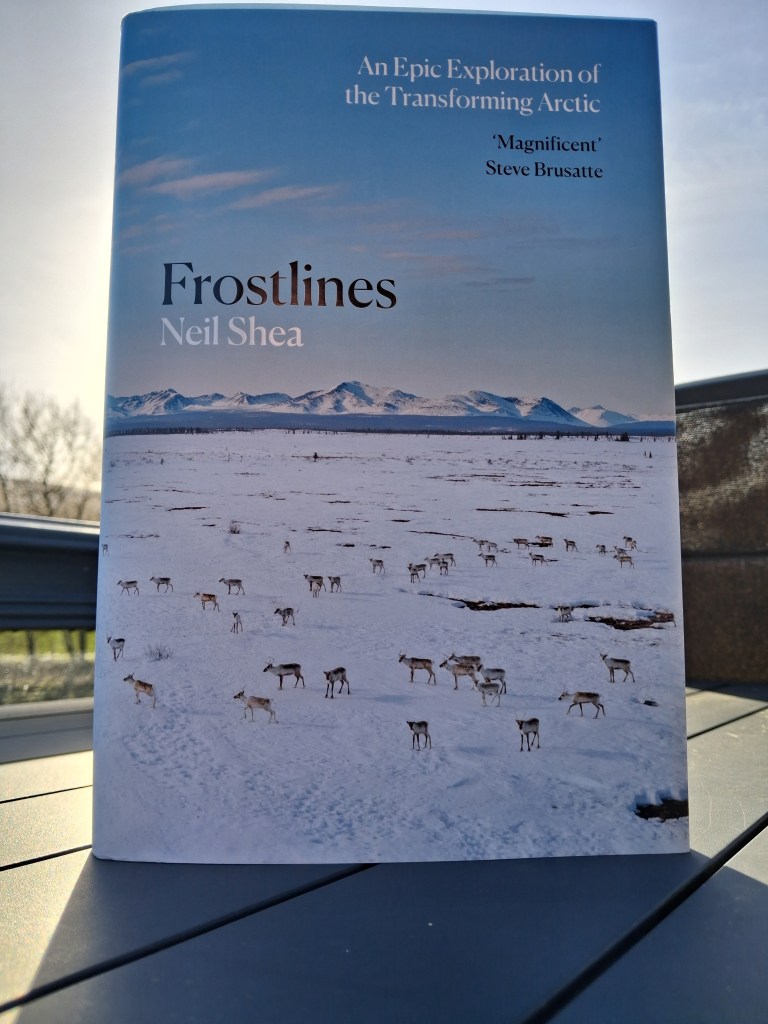

Shea’s trail begins by following the animals of these landscapes, animals which are an equal part of this world. He describes quasi-spiritual moments among narwhals, wolves and caribou hunts and begins to cast this relationship as a form of pilgrimage and in choosing to immerse yourself in this pilgrimage, the sense of belonging and identity grows.

The Great Vanishing

Shea moves us away from the ‘southern’ duality of predator and prey thinking about the relationship between animals and humans. ‘Here instead were fellow citizens, travelling through time, over the land, together.’

More importantly, he argues that living with animals becomes an indelible part of your identity and when the herds shrink and disappear, more is lost than just the wildlife. ‘If you are a caribou people and your caribou disappear, what do you become?’ The reasons for this loss do not appear to be clear cut. ‘No one knows that the caribou are disappearing. There’s no consensus on what’s behind this great vanishing. No disease has been pinpointed, no individual culprit gets the blame.’

The language used to describe the landscape of the Arctic may miss out on so much- words like ‘bleak’, ‘empty’, unforgiving’ or ‘arid’, fail to capture the richness of the northern worlds. The Arctic is more than just the visual experience that these earlier words convey and instead, like many landscapes, it contains a history, a presence, and emotional ties that help define who we are.

If we limit and contain our knowledge of any place to merely what can be seen, we miss out on the invisible bonds that create that sense of belonging between a people and a land.

‘The land isn’t barren, it’s busy with the memories of caribou.’

The collective sigh of climate change

That this relationship between place and people is changing is in no doubt. Shea draws on his own experiences of the Arctic when he notes, ‘The Arctic I saw in 2005 no longer exists. Innumerable changes have unfolded since I stood on the sea ice in Admiralty Inlet. Most of them have to do with heat, human-caused climate warming, and the fact that today the Arctic is warming three or four times more rapidly than any other region of the planet.’

What this new world means for the peoples of the Arctic, as different vegetation grows, as different species move in and out of this new world, and as passages for humans to move through and exploit, all remains to be seen. As Inuk activist and Nobel peace Prize nominee Sheila Watt- Cloutier notes, “What is happening today in the Arctic is the future of the rest of the world.” Ice is the ‘glue that binds this Arctic world together’ and even from a southern perspective, there is a deep sense of loss that comes, when what was viewed as never-changing becomes fragile and diminished. Shea asks the most relevant of all questions, when he reminds us that what happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic.

‘What can it mean, for all of us, if the north ceases to be cold?’

Walking the land

In reading, or experiencing this book, I am reminded of the proverb, “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man“.

The Arctic is a shifting river of changing time, memory and people. The impact of human society is felt sharply there, whether in the guise of geopolitical threats and posturing from nations wanting to exploit Arctic resources, or from the impacts of climate change.

This is not a text which is a eulogy for a lost world, or the looming mortality of tribal knowledge and customs, nor is it an angry, emotional rant about the effects of ‘Southern’ influence in a landscape to which we don’t belong. Shea sums it up best when he describes a ‘moral relationship’, ‘What indigenous communicates now to me, after my journeys through the north, is a sense of belonging that is not manufactured or purchased but earned. A commitment to moral relationships between humans and land and sea. A respect for the way cold holds everything together.’

He concludes by pushing humanity to the side and focuses on the landscape, the trails, the memories, the opposites which live beside each other in a world where the frost is softly melting. Shea argues that this Arctic world might not end in a catastrophic ‘bang’, but rather in a series of events that end the way of life there, like a door slowly closing.

‘The borders that mattered, I had thought, were not imaginary lines drawn between nation-states that might not survive another century. What mattered were shifting edges of ice and water, earth and stone, trees, light, darkness. Language. The movement of animals.’