-

Rushcliffe Borough Council move forward with housing development on former RAF Tollerton site

Provided by Rushcliffe Borough Council

Rushcliffe Borough Council’s Cabinet met this evening and moved ahead with their Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) as part of the Masterplan for future housing developments on the former RAF Tollerton site.

Campaigners had gathered outside Rushcliffe Borough Council this evening, in an effort to remind the Cabinet of the essential pause that they had decided only a few months ago. In January, RBC had paused their onward decision citing the need for more information on traffic and infrastructure

In a press release that appeared on the Council’s website this evening, RBC stated,

‘The Council’s Cabinet met today (March 10) and passed recommendations on a Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) following consultation last year on its content and having acknowledged the points raised by a local campaign group.

This does not grant any existing or future planning permissions for applications and the SPD will now guide any next stages of development by providing a key development framework and masterplan for the whole of the strategic allocation.

In January, Cabinet had voted to pause a decision on the next stage of planning whilst more detailed information was requested from the developers, especially on highways, which was forthcoming and provided Cabinet with key information regarding an aligned approach to a single highways solution.

Members of an RBC cross-party Councillor working group and Council Officers have worked on adoption of the Masterplan for many years as it brings together a single vision for the comprehensive development of the site.

Cllr Roger Upton, RBC Cabinet Member for Planning and Housing, reiterated that the Council needed an SPD for the site so it can further oversee developers’ plans and have more influence on how they are shaped.

He said: “If we did not pass this SPD we would have risked applications for homes on the site at Gamston and Tollerton being determined by Government rather than by local people.

“We currently have applications submitted to the Council to build on the Gamston and Tollerton site, and we have been clear a Masterplan for the entire development is needed to offer clear guidance on where the infrastructure should be sited as part of the planning process.

“We have now received more information from the developers, and comments from Nottinghamshire County Council and National Highways on the data and plans for the transport and highway solutions in and around the site.

“We have also received confirmation that the developers are continuing to work collaboratively and proactively with each other, and the highways authorities, to identify a satisfactory highways solution.

“As a Council we have called on the Government to abolish housing targets, but this policy does not seem forthcoming, and we have an obligation to have an up-to-date Local Plan and five-year land supply.

“We are aware of concerns around possible contamination on areas around Nottingham Airport, and these must be addressed as part of any planning applications.”

Campaigners outside council offices this evening

‘‘A frankly indefensible’ decision

One of the lead campaigners of the Save Nottingham City Airport Group, Sarah Deacon was scathing of the decision when she told me, ‘Cabinet’s decision to adopt the SPD is, frankly indefensible.

No traffic monitoring. No fixed highways strategy. A live objection from National Highways. And the reason for all of this? Developers chose not to supply the evidence the Council itself required- and the Council proceeded anyway.

When developers can simply withhold essential information and face no consequences- when the planning process continues regardless- it exposes a deeply troubling imbalance of power. It is residents who live with the consequences of these decisions. It is residents who deserve to be at the centre of them.

This Borough deserves a planning process led by evidence and accountability- not one that bends to developers who refuse to provide either.

We are consulting our legal team and will be announcing our next steps shortly.’

Certainly, no new documents have been uploaded to the planning portal since December 2025, leaving residents, campaigners and the wider public in the dark, as to what new information the council has received. It remains difficult for the public to support or object to the delivery of the planning proposals, if they cannot view the most up-to-date information, leaving some feeling that there is a lack of transparency in favour of the developers.

Have the Council exposed themselves to legal risks?

In a press release this morning, campaigners warned that the decision to move ahead with the planning document could undermine the wider Greater Nottingham Strategic Plan, as questions could be raised about how deliverable the housing allocation could be.

“Campaigners warn that pressing ahead in this state would expose the Council to clear legal risk, including potential judicial review, and could seriously undermine the ongoing examination of the Greater Nottingham Strategic Plan (GNSP)—which depends on the allocation being demonstrably deliverable.”

Campaigners had therefore expected this outcome from Rushcliffe Borough Council’s Cabinet and are now considering whether pursuing a judicial review of this decision would be the best strategy.

Have contamination fears been addressed?

Questions and concerns about contamination from the former use of the site as a burial site for Lancasters and other aircraft remain unanswered and campaigners are left hoping that the council will stick to its promise that the radiation contamination ‘must be addressed as part of any planning application.’

Residents who could not attend this evening’s meeting had hoped that Rushcliffe Borough Council would live-stream the meeting, as they have done for other meetings. Unfortunately, this live-stream did not go ahead, leaving residents feeling that they continue to be ignored and dismissed.

With the signal to move ahead granted this evening, residents and campaigners fear that they remain in harm’s way.

-

Review of ‘Plastic Inc.’ by Beth Gardiner

Let’s start with a visual experiment. Look around the room which you are in and see how many objects you can spot which are made of plastic. The television? The television remote? Your laptop? Your phone? Those pesky pieces of Lego?

Which plastics are in your television remote? When you upgrade to a new tv, or upgrade to new plastic, what will you do with your old remote? Can it be recycled? Will you drop it into your recycling and watch it be carted off- relieved that you have ‘done your bit’, without seeing the journey it makes?

In ‘Plastic Inc’, Gardiner urges us to notice and be aware of the tide of plastic objects, which we have been encouraged to bring into our homes and which have quietly taken over. She urges that this is no accident, but a deliberate campaign by fossil fuel companies to maximise their profit- often creating a need for plastic where none existed. ‘The news that big fossil fuel companies were pouring billions of dollars into plans to make more plastic than ever in the years to come-even as so many people, worried about plastic’s proliferation into every corner of modern life, were trying to use less.’

Gardiner argues that this ubiquity of plastic causes distress for many of us, as it has become a global mess, with no end in sight and indeed, production of plastic is ramping up even more to new heights. ‘Plastics’ spread into every corner of our lives is also taking an invisible toll on our health. The chemicals that leach from them have been linked to heart disease, cancer, fertility problems, and even neurodevelopmental issues such as autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.’ She adds, ‘The plastic drenched world we live in today didn’t just happen. It was built by an industry that has slowly, steadily- and stealthily- drawn us into its web. The links between plastics and Alzheimer’s and other neurological diseases, such as Parkinson’s, are being explored with more frequency and more depth, as the rise of these cases continue.

How did we let this happen?

It would be too easy for Gardiner, simply to turn ‘Plastic Inc’ into a long angry rant about the evils of plastic, but she acknowledges the benefits of some of the technology that has been made possible through its manufacture.

‘Of course, this is not a simple story of an evil material. Plastic has many invaluable, even essential uses. I wouldn’t want to live in a world without the medical equipment it makes possible.’

What Gardiner wants to do is to shift the focus from the product itself, to the manufacturers, to the plastic industry that lies beneath the surface- hidden from scrutiny, but in plain sight.

‘While plastic itself is easy to see, the industry bringing it into the world is invisible to most of us. This book aims to shine a light on it.’

The rise of plastics

Shine a light on the industry is done thoroughly by Gardiner, as she charts and chronicles both the rise of industry and of individuals who have ignored the views of the public to foist more unnecessary plastic products on them, to keep us addicted to their product. Gardiner names the fossil fuel companies which are to blame and notes the shift in their output of plastic products as oil demand lessens. She explores the intentionally flawed thinking of the plastic industry, as they encourage consumers simply to ‘recycle’, as if this was a panacea to all the plastic ills. ‘We can’t recycle our way out of the plastics mess.’ She warns that the iconography of the ‘recycling arrows’ has led to consumer confusion, which the industry delights in. ‘Consumers would treat anything labeled with the chasing arrows as recyclable, and flood local systems with material they were unequipped to handle.’

Big Oil created a narrative for the public that all plastics could be recycled and pointed the finger at the public’s behaviour when they couldn’t understand the various PET numbers on plastic packaging. They urged that the public should be educated about how to dispose of their product and emphasised that ‘Plastic is good. Pollution is bad.’ channelling ‘The Crying Indian’ advert for the modern world. ‘What’s more, talk of recycling often focuses on “education” and “behaviour change”- a handy way of shifting responsibility from industry to individuals.

Nothing is ever thrown ‘away’

Another key factor in the plastics waste cycle is that of disposal- a factor which the fossil fuel companies seem very uninterested in. We have all seen images of plastic and waste mountains in Kenya, Indonesia, Malaysia, India and many other countries around the world. Countries which are not equipped to deal with the levels of waste plastic that the Western world produces. ‘When China closed its doors to foreign plastic waste in 2018, it could have been a moment of reckoning- a firm nudge pushing wealthy countries to look clearly at the mess we are creating and find a different path, Instead, from Los Angeles to Rotterdam to Seoul, those with waste to get rid of simply found new places to send it.’

The blame about who was badly managing this problem remained with countries and individuals- the fossil fuel industry has successfully created this shift in blame. That poorer countries around the world are to blame for managing the plastic waste which we create. Shame on them! Who escaped this blame spotlight? Why, the fossil fuel industry once again.

Shifting blame

Gardiner also details the impacts of fracking, endocrine disruptors and microplastics in this wide ranging book- the chemical cocktail which surrounds our lives and poses clear physical risks to humans, marine life and many other life forms on this planet. Fossil fuel companies have unleashed a ‘plastic chemical virus’ on the planet and then have blamed us for its impact. ‘It’s painful to look clearly at the ways huge, extraordinarily profitable companies have foisted plastic on us for decades and convinced us it’s our fault, while wielding their money and power to squelch any efforts to stop them.’

Gardiner acknowledges that solutions won’t be easy unless governments act to regulate an out of control industry. ‘There are no simple answers to the questions posed by plastics’s spread into every corner of our lives.’ She urges us not to give up hope though, as we are being harmed by yet another product of the fossil fuel industry. ‘Reversing plastic’s relentless proliferation, and the harms it is wreaking, won’t be easy, but it’s not impossible either.’

‘A less plastic world can seem like a utopian dream, unrealistic and out of reach. It’s certainly hard to envision after decades in which the trajectory has gone only one way, and we’ve felt so powerless to change it.’

‘Plastic Inc’ allows us to see that this plastic pollution of our world has been a concerted and calculated strategy by the fossil fuel industry over decades, intent on profits at all costs. A strategy which has infiltrated every part of our lives and flooded our world.

-

Will Rushcliffe Borough Council’s upcoming decision force campaigners to seek judicial review?

Tollerton Airfield housing development reaches significant moment

This coming week will see Rushcliffe Borough Cabinet meet again to discuss and decide on a planning decision which will allow for around 4,000 houses to be built on around the former Tollerton Airfield site.

The Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) and its implementation was paused earlier this year, owing to concerns about transparency and a need for new information.

The council stated in January, ‘‘Rushcliffe Borough Council’s (RBC) Cabinet has voted to pause a decision on the next stage of planning at Tollerton Airfield whilst more detailed information is requested from the developers on highways.

It met on Tuesday January 13 and chose to not proceed with a Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) or masterplan for the site at this stage, requesting developers submit more information on highways modelling data that can inform traffic projections.’

Cllr Upton complained about this lack of information, when he commented, ‘“We have been awaiting detailed traffic modelling data from developers, and comments from Nottinghamshire County Council and National Highways on the data and plans for the transport highway solutions in and around the site, and it is yet to arrive.

“We have therefore decided to delay a decision on the SPD whilst we request this information. We do need to make a decision by June 30, 2026 and will be calling upon the developers and highways agencies to provide this information, which they have had months and years to complete.

“We are aware of concerns around possible contamination on areas around Nottingham Airport, and these must be addressed as part of any planning applications.

However, no new information has since been uploaded to the planning portal since then, leaving Save Nottingham City (Tollerton) Airfield campaigners puzzled by this seeming reversal of the council’s own process and priorities.

A house of cards

Campaigner Sarah Deacon, commented, ‘There is nothing new in the ‘revised’ SPD…absolutely nothing. So absolutely nothing that, in fact, the “new” diagram which the developers have included for their proposed access point, is actually 20 months old.’

She continued, ‘Policy 25 of Rushcliffe’s own Local Plan (2014) requires that the proposed development be “appropriately phased to take into account provision of necessary infrastructure, including improvements to the highway along the A52.”

You cannot phase development around infrastructure that hasn’t been designed, costed or agreed. Rushcliffe residents, community groups and stakeholders who engaged with this process in good faith were told the Council needed specific information before it would proceed. That information has not arrived. But, the Council is looking to proceed anyway.

We believe that decision is legally vulnerable and fundamentally premature.”

Preparation for judicial review

Owing to this apparent ‘steamrolling’ of the decision from the campaigners’ perspective, they now claim that this could be open to a judicial review on the grounds of irrationality and are preparing a fundraising event in anticipation of this course of action being needed if Rushcliffe Borough Council do indeed agree that the Masterplan can go ahead, despite the information that they paused the decision for, still not being available.

Deacon summarised this undue haste, when she said, “They said the SPD “could not proceed” because they were still awaiting detailed traffic modelling data. They said they needed comments from Notts County Council and National Highways before making any decision. They stressed this modelling was essential to understand traffic, safety and road impacts. RBC can’t have it both ways. They can’t adopt a document they know is legally vulnerable, call it deliverable, and expect the Inspectors (or the courts) to agree.”

Campaigners gather outside council offices in 2025

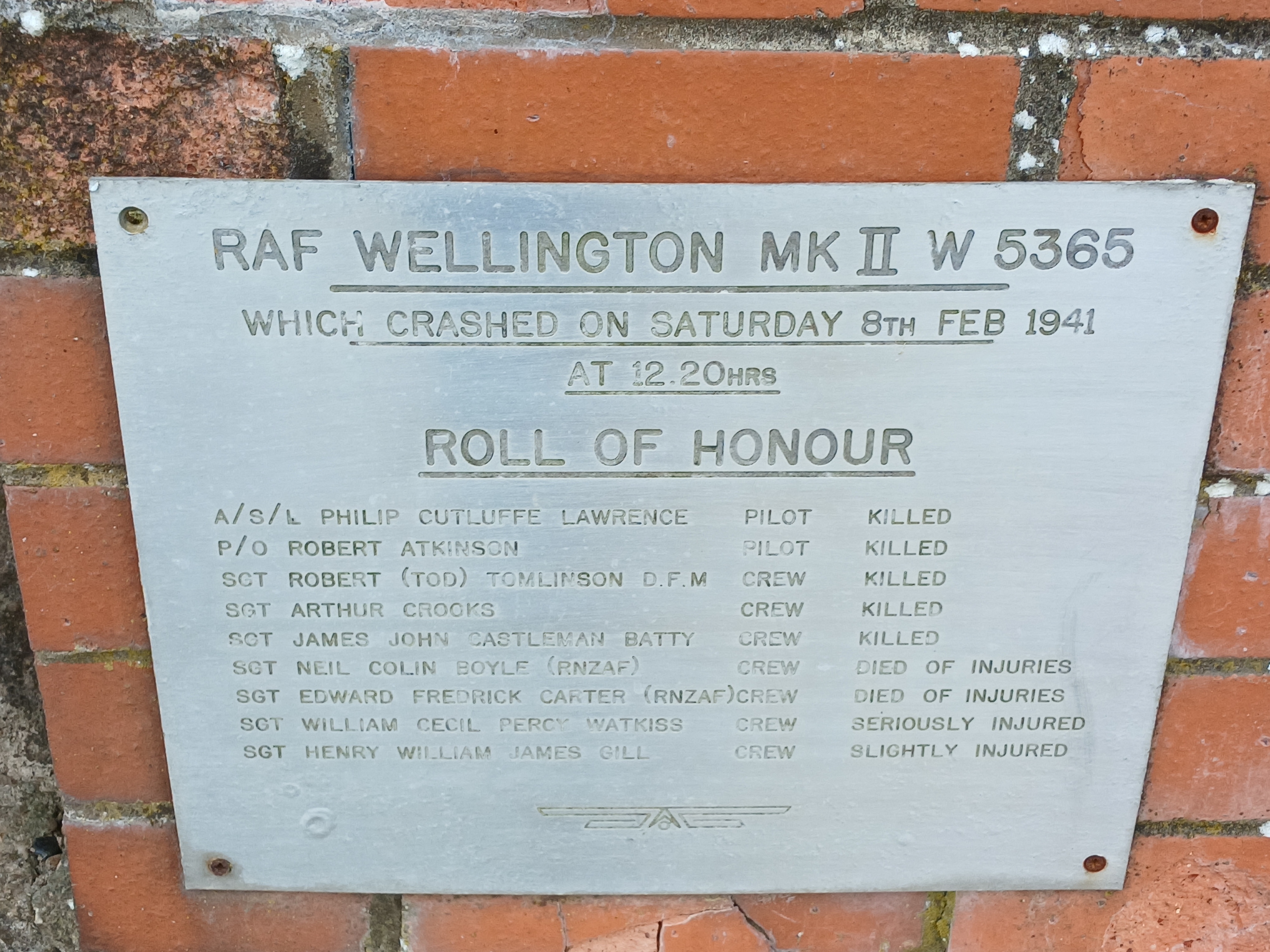

Contamination of Tollerton Park

Residents and campaigners alike fear the conclusions of a 2008 investigation into radiation contamination- a document that presently appears on Rushcliffe Borough Council’s own website– which indicated areas of radium-226 contamination. ‘The caravan site at Tollerton is situated on a decommissioned Royal Air Force Air Base. After the Second World War it was used as a base to demolish Lancaster bombers. A particularly significant part of this process was the disposal of the luminising dials from the cockpits. Radium was used universally in the first half of the 20th century in dials, watches, etc. The disposal of the luminised instruments from aeroplanes generally took the form of burning or burial. The migration of radium to the environment from such practices is documented.’

Two areas of radiation were detected- one in the grounds of the airfield, which is being proposed for the housing development. ‘However, two areas of radium-226 contamination were detected outside this area: one in the airfield just outside the perimeter of the site, and one in the caravan parking area.’

The national press also highlighted the radiation fears of some residents of Tollerton Park, ‘All we want now is a thorough, invasive survey done on the park for a clean bill of health. We just want answers. We want to live a peaceful life. We came here to retire, not to fight the council.’

In November 2025, only a few months ago, the UK Health Security Agency urged that there was ‘suitable justification’ for another radiation survey to take place on Tollerton Park, just north of the former Tollerton Airfield site. They stated, ‘Consequently, we suggest that RBC consider attaching a condition to the planning application that requires the developer to have plans in place in case any contaminants are uncovered during works so that any risks to health posed by those contaminants, both to the developers own employees as well as to future users of the land, are suitably managed.’

No such condition yet exists on the planning portal.

Military monument to World War 2

All local, regional and national eyes will be on Rushcliffe Borough Council’s decision this coming week, as it clear that they have knowledge of the radiation contamination on the proposed housing development site; do not appear to have received the detailed traffic monitoring date that they were waiting for; and have not made public any information gathered from Nottinghamshire County Council.

To approve the planning application for the large housing development with this significant and necessary information missing, could leave RBC open to the planned judicial review, which in turn would create more delay and pose unwelcome legal questions for the council.

-

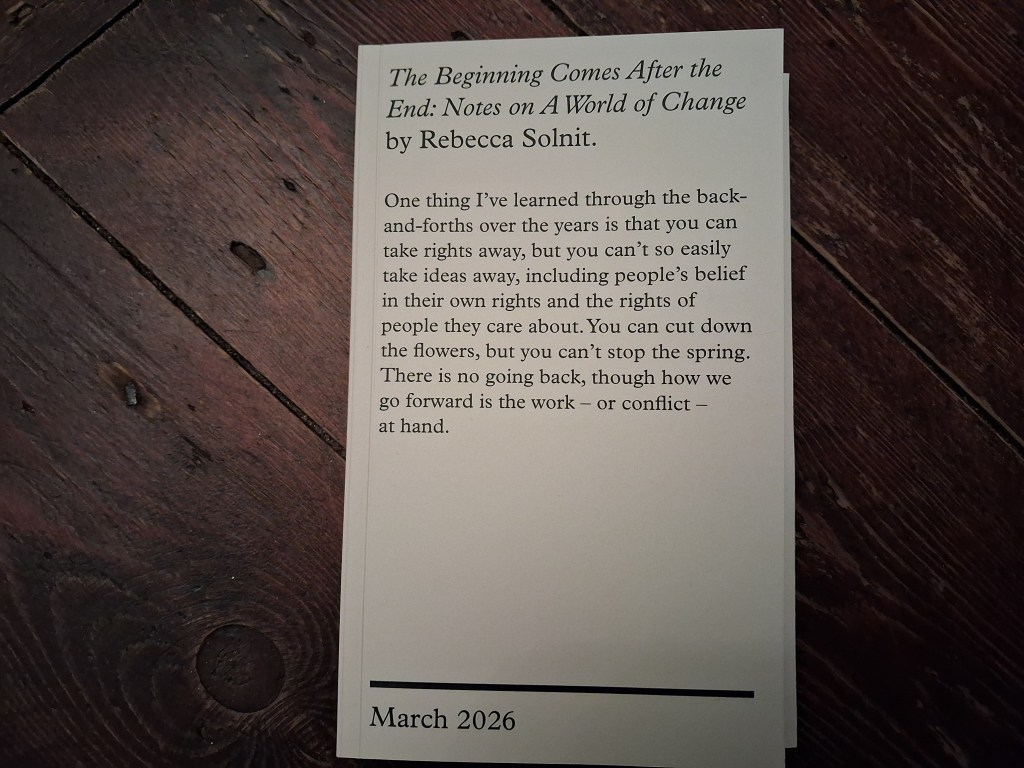

Review of ‘The Beginning Comes After the End: Notes on a World of Change’ by Rebecca Solnit

When Solnit speaks, the world should listen.

Her writing, spanning the years, has echoed with a deep personal voice, rooted in place, as well as optimistic activism. She charts and traces the changes that have transformed society and the world in the past, and reminds us that the power to change the world is within our reach and lies within us all.

This is not a ‘radical’ book- unless the power of ideologies and stories is radical in itself. Solnit has mastered the power of language long ago and the clarity and vision with which we have come to expect from her, resonates once again. Without doubt, this is a powerful vision which she lays out in ‘The Beginning Comes After the End’, one, which if adopted as a blueprint for the 21st century, would create a world and societies that would be worthy of the human race. This ‘blueprint’ would be, ‘A shift towards the idea that everything is connected, that the world is a network of inter-related systems, that the isolated individual is at best a fiction, and that the natural and social realms run more on collaboration and cooperation than competition.’

There are too many of us who are rooted in the last century- whose birth year begins with ‘19__’. We straddle both the past to which we are tethered and anchored, while the 21st century stretches out ahead of us- waiting for us to be the good ancestors for those who follow our footsteps along the path of our species. Solnit reminds us that, ‘We in the 2020s live in a world that would be unbelievable and maybe inconceivable to people sixty or seventy years earlier.’

As I read these words, I think of my father in his last 80s. Born in 1939, on the cusp of the Second World War- an event which defined the 20th century in so many ways- I think that his world and my world are incredibly different and that the changes since the mid-20th century are too numerous to mention. The changes which would have beyond his generation’s ken and yet, which we take for granted on a daily basis. Yet, Solnit does not ask us to romanticise the past or to wish to recreate a ‘lost world’, with all its attendant baggage. Indeed, she warns against this. She argues that choosing to allow ourselves to listen to the lessons from the past, can bring us out from beneath the shadows of the past into a new world. ‘But it’s the past that shows us the possibilities, how the world has changed, how power can appear in places and among peoples assumed to be powerless and irrelevant, how the most foundational things can be transformed’

‘We are such stuff as dreams are made on’

We all imagine and believe that the future will be different, but perhaps don’t realise that we could be the agents of these changes. As Madonna Thunder Hawk reminds us: “We’re the ancestors of tomorrow.” Solnit herself comments that incremental changes can collectively change the course of history and the future. ‘I’ve lived through a lot of the changes they helped launch, most of them happened so incrementally that they unfolded invisibly, but a thousand steps add up to a considerable distance.’ She urges us to accept what history has shown us- more clearly than anything else- that change is possible. That the ideas cemented into the fabric of our identity and society can be broken and disturbed. ‘Our world has changed more than almost anyone imagined, in ways both wonderful and terrible, often in ways no one anticipated, and the sheer profundity of change in the past guarantees that this change will continue.’

The only constant that is guaranteed is that change happens. ‘Change is a constant, but social change has sped up in our time, altering the very fundamentals of how we think about ourselves and the natural and social worlds, and also who defines what “we” means.’ She identifies the social nudges of change, which have helped us build towards integration and interconnected relationships, rather than a distancing and ‘othering’ ‘Changes build on changes; one shift makes another possible.’

We are not at the end of history, says Solnit- we are simply the navigators in the middle of the journey- the creators of a new story. A story which will shape what the future looks like as we move through the time of this century. A simple task may be for us to try and pierce the mists of time and to imagine what the world could be like by 2100. How would that be accomplished? What, or who, would be the catalysts for this new direction? How many false starts and stumbles would happen along the way? ‘This is a reminder that you do not have to picture the destination to reach it or at least draw closer to it, you just need to choose a direction and keep on walking…’

‘A new heaven and a new earth’

Solnit quotes the words of Antonio Gramsci, when she argues that the birthing of this new changed world is a slow process. ‘The old world is dying. The new one is slow in appearing. In this light and shadow, monsters arise.’ She contends that ideas and stories have power- a power feared by those who wish to cling to the wreckage of the old world, for fear that who they are will be lost. ‘Ideas have power, and while those who support them often dismiss that power, those who fear them recognize they can change the world.’ She also notes the wisdom of Thomas Berry, when she acknowledges that the lack of a certain future path appears to some as though the path does not exist at all. Lack of certainty is not lack of existence.

“We are in trouble because we do not have a good story. We are in between stories. The Old Story- the account of how the world came to be and we fit into it- is not functioning properly and we have not learned the New Story.”

For Solnit, the power of stories can create new ‘forests of possibility’ and it is in this ‘possibility’ where new worlds dare to breathe. What is wonderful is that this imagery continues, as Solnit exhorts us to root ourselves in the past to reach the future.

‘What if our best hope reaches for the future by sinking its roots deep in the past? What futures can we build on these other versions of the past, these other voices with other stories to tell? What beginnings come after such an end?’

A Brave New World

As I look at the sleeping face of my 8-years-old son, I imagine the world of 2100, a time where he will almost be the same age as my father is now. It is a world which I cannot imagine, but one which I know will be different from this one.

I cannot walk with him into that brave new world, but I can hold his hand for as long as possible, to be his guide, until he carries his own dreams of change. I am reminded of the popular motivational poster that once was displayed in his room- ‘Let him sleep, for when he wakes, he will move mountains.’

I know that he will move these mountains, not by scaling the heights in a dangerous, desperate rush, but by slowly moving one stone at a time.

‘The Beginning Comes After the End: Notes on a World of Change’ is the most personal and uplifting book about the power of ideas and about our ability to be transformed.

We are all dreamers.

“We are living through a revolt against the future. The future will prevail.”

–Anand Giridharadas

-

Yorkshire to decide fracking proposal and not the Government

Secretary of State declines to call in Burniston fracking proposal

River Ure in Yorkshire Proposals for fracking near Scarborough will now not be ‘called in’ by the Government and instead the decision will remain with North Yorkshire Council.

The Europa Oil & Gas proposal suggested using a “proppant squeeze” method to extract gas through a 38m drilling rig. However, after the application was postponed almost a month ago for the plans to be considered by the Housing Secretary, the recent news is being processed by local campaigners, who are fearful that the focus on the decision maker is the wrong call. John Atkinson, one of the leading campaigners of Frack Free Scarborough said, ‘It doesn’t matter who makes the decision, fracking is so bad and so universally hated that if it’s ever passed, people will not stop fighting until it’s dead and buried.’

The Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government Committee said last week

“The secretary of state has carefully considered the policy on calling in planning applications, as set out in the Written Ministerial Statement dated 26 October 2012. The policy makes it clear that the power to call in a case will only be used very selectively.

“This policy also gives examples of the types of issues which may lead him to conclude, in his opinion, that the application should be called in. The secretary of state has decided not to call in this application.”

‘Patriotic duty’ to embrace fracking says Reform UK

The Deputy Leader of Reform UK, Richard Tice, told GB News last week that Britons have been “deeply misled over misinformation” about fracking. He claimed that shale gas would mean lower bills for consumers and agreed with Rees Mogg’s assertion that ‘Fracking is a perfectly safe process.’ He continued that it was our ‘patriotic duty’ to embrace fracking. “Let’s be patriotic and say, I want Lincolnshire gas for Lincolnshire jobs and Lincolnshire growth. I want Yorkshire gas, for Yorkshire jobs and Yorkshire growth. This is our patriotic duty to our children and our grandchildren.”

Reform’s Andrea Jenkyns has recently been courting American fossil fuel companies keen to bring fracking to Lincolnshire, which is bizarre considering the UK Government’s ban on fracking.

Tony Bosworth, climate campaigner at Friends of the Earth, disputed these claims from Richard Tice when he said: “The government still has a key role to play in the fate of this planning application. Labour has promised to ban fracking – and this highly controversial and deeply unpopular proposal involves a low-level form of fracking called proppant squeeze.

Ministers must ensure that proppant squeeze is included in its forthcoming ban, update national policy accordingly, and ensure communities like those in Burniston are not forced to accept damaging developments in their local area.

Fracking blights our countryside, won’t cut UK energy bills and is deeply unpopular with local communities. This application should be rejected.”

The irony is that on a regional level, Reform-led councils have indicated that they do not want fracking to return or begin. Only a few months ago, Lancashire County Council said that there were no plans for fracking to take place there. Perhaps national rhetoric from Reform UK would do well to listen to its own councils and regions.

Fracking won’t cut our bills say LSE

Reform’s claims on safety and lowering bills have also been called into question previously by the London School of Economics. Bob Ward, policy and communications director at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics and Political Science, said: “The decision to lift the moratorium on fracking does not seem to be based on the evidence presented in the report by the British Geological Survey. The moratorium was introduced in November 2019 after an assessment by the Oil and Gas Authority concluded that earthquakes of magnitude 3.5 or higher triggered by fracking could not be ruled out. Such events could potentially damage nearby buildings. The new report by the British Geological Survey presents no conclusive evidence that such events can now be ruled out.

“As long as the UK consumes natural gas there are good environmental and economic reasons to use domestic supplies of shale gas in preference to importing liquefied natural gas from other countries. However, this only makes sense if the shale gas can be extracted safely. Today’s decision appears to be based on the assumption that a higher level of risk to households is now acceptable.

“In any case, the decision to lift the moratorium on UK fracking will make no difference to the wholesale market price of natural gas and will not ease the cost of energy crisis.”

Farmland contamination

As well as Reform’s arguments not matching LSE analysis, land contamination of farmland through fracking remains a real concern. For a political organisation so supportive of British farmland- it seems once again at odds with their rhetoric when fracking contaminates the land.

Fracking operations in Lancashire at Preese Hall and Preston New Road have raised serious concerns about radioactive waste, water contamination and seismic activity. There have been delays in returning former fracking sites to usable farmland, with the energy firm Cuadrilla asking for extensions, and in turn blaming the Environment Agency for the slow progress.

Reform- led councils don’t want fracking. Communities don’t want fracking. The UK Government doesn’t want fracking. Despite all this, leading Reform figures continue to create division over a topic which has already been settled. -

Human- caused climate change increases rain intensity in Western Europe

Humans are now ‘fighting a humanitarian crisis driven by a changing climate.’

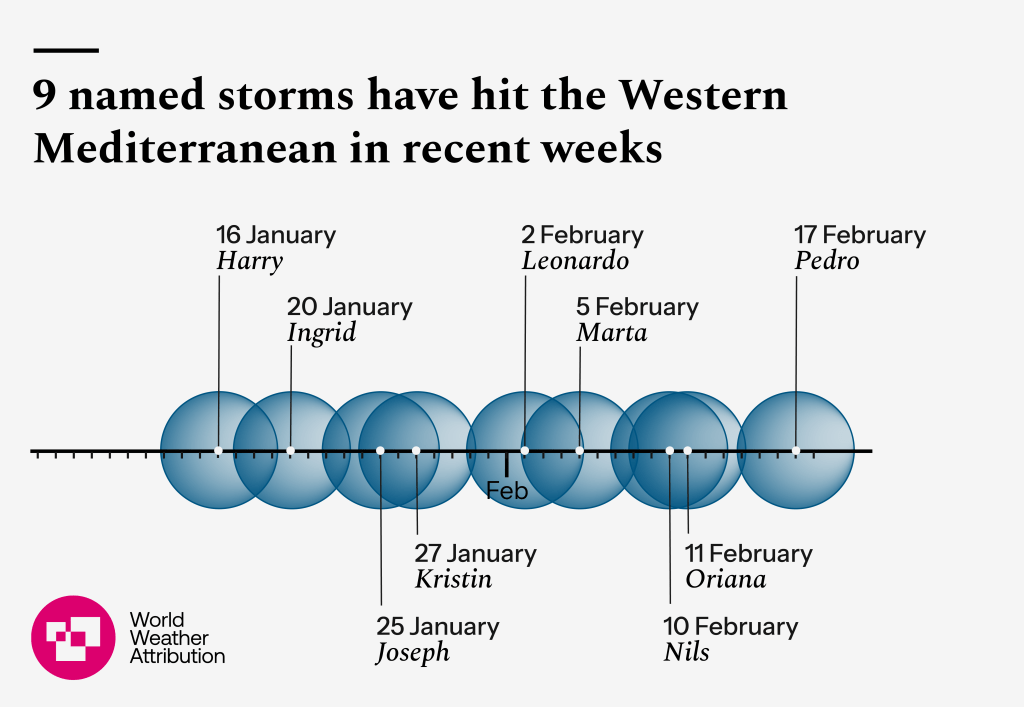

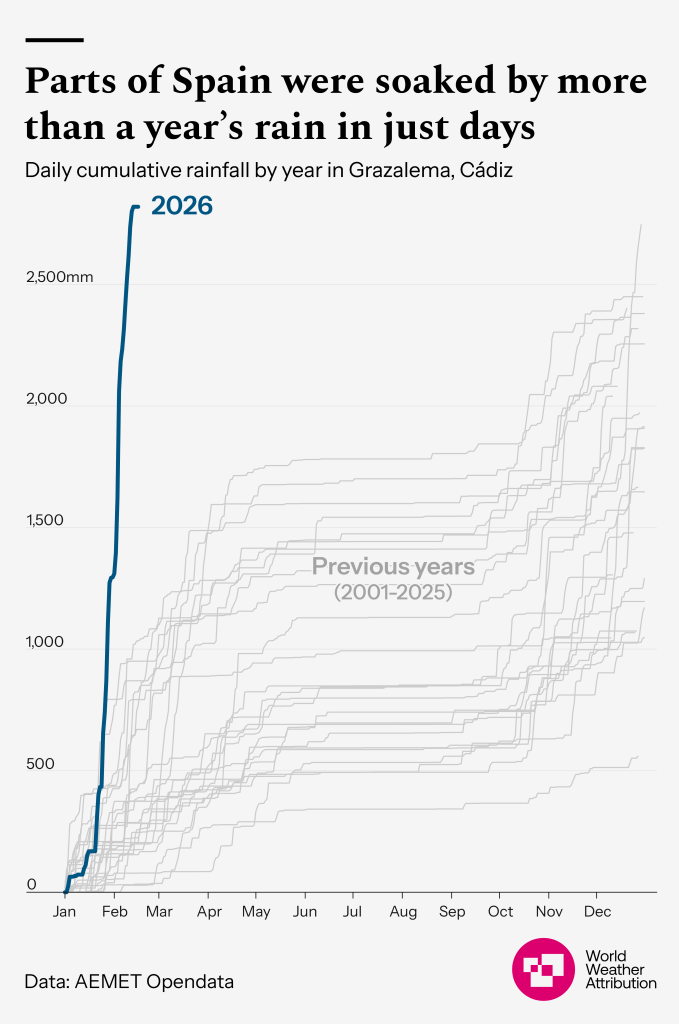

Key findings from a recent World Weather Attribution study concludes that human-caused climate change has increased the intensity of the torrential rain that led to flooding across Western Europe.

Researchers identified a clear trend showing the wettest days are now around a third wetter than they were before the planet warmed by 1.3°C.

The study found that ‘An unusually high number of named storms have brought hurricane-force winds and dumped huge amounts of moisture on the region since mid-January, causing over 50 deaths, displacing hundreds of thousands in Morocco, Spain and Portugal and causing billions of Euros in damage.’

9 named storms in 2026 in recent weeks

The study focused on the displacement of people in Western Europe owing to the relentless storms, with hundreds of thousands displaced in Northern Africa.‘Since 16 January, nine named storms have battered the Mediterranean region, bringing torrential rain and high winds that forced the evacuation of more than 12,400 people in Spain, 3000 people in Portugal and 300,000 people in Morocco.”

As well as displacement in Morocco, the study found that ‘flooding caused 43 deaths, displaced 300,000 people and inundated 110,000 homes, prompting a €280 million recovery plan.’

A ‘dangerous blueprint’

Dr. Clair Barnes, Research Associate in Extreme Weather and Climate Change at the Centre for Environmental Policy, Imperial College London said: “While trends in extreme rainfall are quite mixed across the Iberian Peninsula and Northern Morocco, in some parts of the region we are seeing dramatic increases in extreme rainfall that are attributable to human-driven warming.’

She continued, ‘The strong observed increases in some regions should be a warning for us. We know that a warmer atmosphere carries more moisture, and so the more carbon we emit, the more dangerous the blueprint will be for winter storms like these.’

Every fraction of a degree matters

Dr. Friederike Otto, Professor of Climate Science at the Centre for Environmental Policy, Imperial College London said: ‘This is exactly what climate change looks like: weather patterns that used to be more manageable are now turning into more dangerous disasters.

‘Whether it is the 11% increase we’ve been able to directly attribute to human activities, such as our burning of fossil fuels, or the much higher trends we see on the ground over the decades, we’re confident that climate change makes these intense downpours more severe.’

She continued, ‘We have the tools and knowledge to stop this getting worse but we need the will to roll them out faster and change our societal systems for the better. Every additional fraction of a degree of warming is worth fighting for or the downpours will only get worse.’

A year’s worth of rain in just a few days

Spain experienced a shocking start to 2026 with rainfall exceeding levels from the last twenty years. This level of rainfall has now become so extreme that it is challenging records which would suggest that this level would be a once-in-a-century event. All too recently, these once-in-a-century events are becoming more regular, challenging our expectations that the present climate extremes may not match previous records suggesting that more warming is leading to more extreme, more intense rainfall, leading to increased flooding risks.

‘In Grazalema, southern Spain, more than an entire year of expected rain fell in just a matter of days. Similarly, parts of Morocco and Portugal saw one-day rainfall totals during Storm Leonardo that are so extreme they would be expected at most once in a century.’

Defences are being overwhelmed

This study of the recent flooding highlighted the need for investment in defences and early warning systems to better protect the public from risks. We have not seen the last of these intense floods and as the planet continues to warm, the risks intensify.

Maja Vahlberg, Technical Adviser, Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre said:

“The lives lost and the hundreds of thousands displaced across Morocco, Spain, and

Portugal are a tragic reminder that our defences are being overwhelmed. While early warning systems have improved, it is a major challenge to fully protect people when rain falls with this level of intensity.

“We must invest urgently in local capacity and ensure that urban planning accounts for a future where what is considered ‘extreme’ is shifting with each year that passes. We aren’t just fighting a change in weather, we are fighting a humanitarian crisis driven by a changing climate.”

2026 may only be beginning, but extreme weather continues to worsen, without an end in sight.

-

‘Not Nimbyism’: Campaigners Fight 20-Turbine Wind Project in Yorkshire Dales

Will the Yorkshire Dales be ruined by renewables?

Barningham Moor Fred. Olsen Renewables have identified a site right on the edge of the Yorkshire Dales near to Richmond, where they hope to erect approximately 20 wind turbines on a peatland moor. This project would generate more than 100MW of renewable energy and would generate enough power for 81,000 homes and businesses, claim the developer.

The site would cover approximately 1,130 hectares and the initial design of the wind turbines appear to be around 200 metres high, or approximately 656 metres. The typical height of a wind turbine in the UK tends to be lower than this 200 metres, with an average of over 50- 150 metres. As a comparison, the Whitelee Wind Farm near Glasgow in Scotland, and the largest windfarm in the UK, measures between 110-140 metres and has approximately 215 turbines generating 539MW capacity.

Peat on the moor With two rounds of public consultation planned for later in 2026, this application from Fred. Olsen Renewables for Hope Moor windfarm will proceed through a Development Consent Order (DCO) rather than a standard planning application, with the decision whether to grant consent resting with the Energy Secretary, the Rt Hon Ed Miliband MP.

Miliband announced contracts for many renewable projects only this month- with 28 onshore wind projects planned, 12 offshore wind projects planned, as well as 157 solar projects planned, so campaigners fear that Hope Moor will be ‘green lit’ by the Energy Secretary as part of the renewables drive, and that although their views may be listened to, that this project may already be a done deal, as far as the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero is concerned.

Energy Secretary Ed Miliband said:

‘These results show once again that clean British power is the right choice for our country, agreeing a price for new onshore wind and solar that is over 50% cheaper than the cost of building and operating new gas.

By backing solar and onshore wind at scale, we’re driving bills down for good and protecting families, businesses, and our country from the fossil fuel rollercoaster controlled by petrostates and dictators. This is how we take back control of our energy and deliver a new era of energy abundance and independence.’

‘Certainly not a case of nimbyism’

A local campaign group against the proposed windfarm was created around 5 months ago- Hope Moor Wind Farm Action Group (HMWFAG) to both raise awareness of the project in and beyond the local community and also to try and stop the development going ahead. Suzy and Tim Wilson, lead campaigners of the group, told me that their main concern was ‘the enormous scale of the development under NSIP procedures, where all the processes work in favour of the developer and Department of Energy and local authority and community voices are largely irrelevant.’

They continued their concerns saying, ‘We are privileged to live in a beautiful place on the North Yorkshire Moors which have been treasured and nurtured for generations and provide a wildlife haven which will be desecrated for future generations and possibly forever if the development goes ahead…This is certainly not a case of nimbyism but of deep sadness that such a stunning landscape could be ruined forever in an accelerated process which bulldozes through all previous planning and wildlife protections.

Vast swathes of this beautiful Island have already been ruined and we want to preserve the wild beauty of the moorland and not see it turned into an industrial energy park to the detriment of the millions of visitors who visit the North Yorkshire Moors, The Yorkshire Dales, Teesdale and the North Pennines each year to enjoy the amazing views and wildlife.’

Political or environmental protest?

A significant number of posts in the online campaign group do give the appearance of having more of a political objection to the proposed windfarm, rather than an environmental argument. This may be the case however, owing to a lack of detailed information from statutory consultees at this early stage in the process. Numerous posts from ‘Reform Against Net Zero’ and the website ‘The Daily Sceptic’- which is well known for pushing misinformation on vaccines, COVID and climate change- appear to be focusing more on anti-wind power in general, rather than objections to this particular proposal. When asked whether the Wilsons felt this diluted and weakened their argument, they said, ‘We do try to monitor the content and hold back anything misleading, but it is a forum for sharing.’

They added, ‘The Action Group is entirely non-political and 100% environmental and has no agenda other than to protect the beauty of the wildlife and moorlands for future generations by preventing this industrial development on a totally inappropriate site.’

They claimed that none of the members of the campaign group were anti-renewable energy per se, but just that they objected to the proposed 20 turbines near their village, on the moor. ‘We have members across the political spectrum and no member is anti-renewable energy.’

Early stage in process

Kelly Wyness, Senior Project Manager at Fred. Olsen Renewables, highlighted the early stage in the process, when he said:

“We’re at an early stage in developing our proposals for Hope Moor Wind Farm. From the outset, we’ve been aware of both the sensitivities of the site and its genuine potential to contribute to UK energy security.

As with our projects in Scotland, Hope Moor will deliver new renewable power, support local jobs and skills, and provide funding for moorland and environmental stewardship, cultural heritage and local communities.

As we move forward, we’re committed to shaping the project with the community. In the spring, we’ll share our early plans as part of a first stage of public consultation, giving people the chance to see the proposals, ask questions, and help influence how Hope Moor can deliver for the community and the country as a whole.”

Whitelee Windfarm, Scotland -

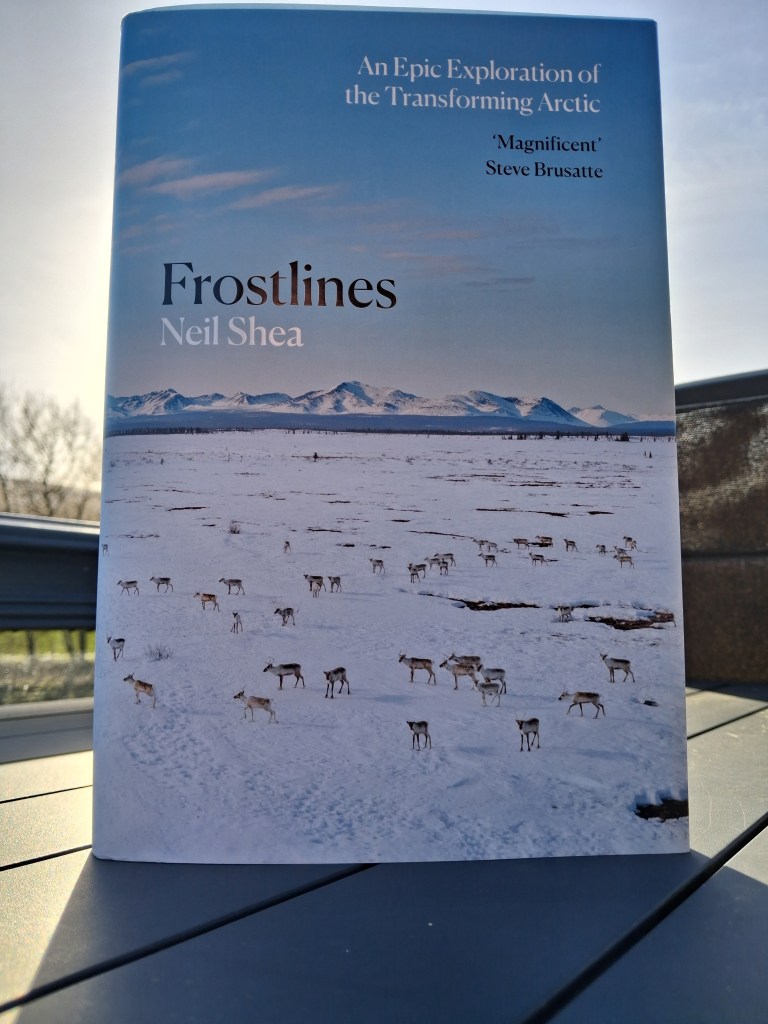

Review of ‘Frostlines’ by Neil Shea

Shea becomes the go-between to introduce us to a new world- or rather, an old world. A world full of culture, history, movement and memories, which is on the verge of being lost.

Shea wishes to ‘bear witness’ to life in the Arctic and to allow all us ‘southerners’ to experience the harsh beauty of life there. He acknowledges though that a new Arctic is emerging and its peoples are torn between adapting to the emerging new world and looking back to preserve and hold tight to the traditions of the past. From Ellesmere Island to the Northwest Territories to Alaska, Norway and Grøenland (Greenland), Shea takes the reader on a deeply personal journey, exploring the liminal spaces and thresholds which exist in the various Arctics. Through the eyes of those not living in the Arctic, there is only one Arctic, but for its peoples, the landscape is charged with different tribes, languages and histories. ‘Four million people living in the region. Some four-hundred thousand of them are Indigenous. Dozens of languages, dozens of tribes and nations and homelands, all of them scattered across just eight modern states.’

Shea’s trail begins by following the animals of these landscapes, animals which are an equal part of this world. He describes quasi-spiritual moments among narwhals, wolves and caribou hunts and begins to cast this relationship as a form of pilgrimage and in choosing to immerse yourself in this pilgrimage, the sense of belonging and identity grows.

The Great Vanishing

Shea moves us away from the ‘southern’ duality of predator and prey thinking about the relationship between animals and humans. ‘Here instead were fellow citizens, travelling through time, over the land, together.’

More importantly, he argues that living with animals becomes an indelible part of your identity and when the herds shrink and disappear, more is lost than just the wildlife. ‘If you are a caribou people and your caribou disappear, what do you become?’ The reasons for this loss do not appear to be clear cut. ‘No one knows that the caribou are disappearing. There’s no consensus on what’s behind this great vanishing. No disease has been pinpointed, no individual culprit gets the blame.’

The language used to describe the landscape of the Arctic may miss out on so much- words like ‘bleak’, ‘empty’, unforgiving’ or ‘arid’, fail to capture the richness of the northern worlds. The Arctic is more than just the visual experience that these earlier words convey and instead, like many landscapes, it contains a history, a presence, and emotional ties that help define who we are.

If we limit and contain our knowledge of any place to merely what can be seen, we miss out on the invisible bonds that create that sense of belonging between a people and a land.

‘The land isn’t barren, it’s busy with the memories of caribou.’

The collective sigh of climate change

That this relationship between place and people is changing is in no doubt. Shea draws on his own experiences of the Arctic when he notes, ‘The Arctic I saw in 2005 no longer exists. Innumerable changes have unfolded since I stood on the sea ice in Admiralty Inlet. Most of them have to do with heat, human-caused climate warming, and the fact that today the Arctic is warming three or four times more rapidly than any other region of the planet.’

What this new world means for the peoples of the Arctic, as different vegetation grows, as different species move in and out of this new world, and as passages for humans to move through and exploit, all remains to be seen. As Inuk activist and Nobel peace Prize nominee Sheila Watt- Cloutier notes, “What is happening today in the Arctic is the future of the rest of the world.” Ice is the ‘glue that binds this Arctic world together’ and even from a southern perspective, there is a deep sense of loss that comes, when what was viewed as never-changing becomes fragile and diminished. Shea asks the most relevant of all questions, when he reminds us that what happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic.

‘What can it mean, for all of us, if the north ceases to be cold?’

Walking the land

In reading, or experiencing this book, I am reminded of the proverb, “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man“.

The Arctic is a shifting river of changing time, memory and people. The impact of human society is felt sharply there, whether in the guise of geopolitical threats and posturing from nations wanting to exploit Arctic resources, or from the impacts of climate change.

This is not a text which is a eulogy for a lost world, or the looming mortality of tribal knowledge and customs, nor is it an angry, emotional rant about the effects of ‘Southern’ influence in a landscape to which we don’t belong. Shea sums it up best when he describes a ‘moral relationship’, ‘What indigenous communicates now to me, after my journeys through the north, is a sense of belonging that is not manufactured or purchased but earned. A commitment to moral relationships between humans and land and sea. A respect for the way cold holds everything together.’

He concludes by pushing humanity to the side and focuses on the landscape, the trails, the memories, the opposites which live beside each other in a world where the frost is softly melting. Shea argues that this Arctic world might not end in a catastrophic ‘bang’, but rather in a series of events that end the way of life there, like a door slowly closing.

‘The borders that mattered, I had thought, were not imaginary lines drawn between nation-states that might not survive another century. What mattered were shifting edges of ice and water, earth and stone, trees, light, darkness. Language. The movement of animals.’

-

Review of ‘Despite It All. A Handbook for Climate Hopefuls.’ by Fred Pearce

‘With all its sham, drudgery, and broken dreams, it is still a beautiful world.’ In ‘Despite It All’, Pearce offers us a more hopeful narrative to counter the daily deluge of climate crisis stories from around the world. Pollution of our seas, pollution of our atmosphere, extreme weather, droughts, biodiversity in crisis- it is all too easy to slip into a passive acceptance of the conditions of our world in 2026 and imagine that this is the only future. As Pearce acknowledges, ‘It is easy to be defeatist about the fate of the planet.’

Pearce is at pains not to underestimate the climate trajectory that we are on, but reminds us that stories which uplift with hope resonate more than stories that are filled only with darkness. In the midst of winter, we look for the light of nature. ‘Nothing in this book is an argument for complacency. My purpose is to shine a light on solutions and offer hope in dark times’

He focuses on 7 key areas as his takeaways- the power of nature to find a way; the importance of Indigenous wisdom and knowledge in a modern world; the benefits of technology; community driven projects and land ownership rather than private enterprise; eco-restoration solutions; the end of materialism; and that the population of the world will not rise for ever.

Wildlife means wildlife

‘Despite It All’ begins by focusing on the loss and threats facing nature and highlights that the human idea of ‘wildlife’ often has a visual of pristine environments, rather than dark forests or disused military junkyards, where species often thrive.

‘The scale of humanity’s impact on the natural world is staggering.’

Pearce makes the argument that we tend to believe what we repeatedly hear and if we hear negative story after negative story on biodiversity loss, then we stop looking for the ‘green shoot’ stories. ‘Why don’t we hear more about these amazing cases of nature fighting back and creating the new wild? It is on this argument that this book rests- that although global awareness and public information of the climate crisis is perhaps the highest it has ever been, that positive news stories about eco-regeneration often don’t make the headline news.

The role of technology

Pearce fully unpicks the thorny issue of the role of technology in playing a positive part in offering solutions to some of the climate issues. He bluntly addresses the dangers of viewing technology as some sort of geoengineering ‘silver bullet’, which would only allow for fossil fuel companies to continue with their focus on profits at any cost. He warns about ‘…the potential for obfuscation by corporate players anxious to preserve their profits is immense. For them, every day of delay is a victory.’ He instead makes the point that the technology to make renewables a reality has moved us far aware from continued reliance on dangerous fossil fuels and uses examples of off-shore windfarms, and the rise of solar technology as clear areas of technology being our friend.

We are far more cooperative than we often imagine.

‘Despite It All’ is deliberately a short book. The answers to how we can solve and mitigate the worst of the climate crisis are well known. The ‘technology’ to solve this global crisis is there, the support for climate action from the world’s citizens is there, the need for a change is there- the last domino to push over is political will. In reality, with global political cooperation to push back against the chokehold of the fossil fuel companies, this really would be the last obstacle to overcome.

Of course, all this rhetoric could pale into comparison tomorrow, when the floods come, when the crops fail, when more species become extinct, or when drought tightens its grip. But the climate progress we have made over the past 30 years needs to be emphasised and celebrated. Pearce concludes, ‘The worst could still happen, but it doesn’t have to…I have faith in humanity’s ingenuity and collective will.’ He reminds us that throughout history we have faced seemingly insurmountable mountains before, but that we have always been brave enough to take that first step.

‘But many things that appear unstoppable can be halted and reversed, if we have the will to try.’

‘Despite It All’ reminds us that we have the agency to bring a new world into being. Giving up when we hear the worst of the climate news from around the world and falling victim to a ‘doomist’ narrative, forgets the lessons to us from nature- that spring always follows winter and that the light always returns to the world.

“Another world is not only possible, she is on her way.

On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.”

–Arundhati Roy

-

Yorkshire Water Bills Rise Again as Customers Pay for Upgrades

The lack of outrage over water companies raising customer bills again, reflects the stranglehold they have on the nation.

The annual bill for Yorkshire Water customers is set to rise this April by over 5% for the average household bill. This would mark a rise on the average property from £602 to £636 per year.

The news passed last week with barely a whimper of protest from Yorkshire Water customers, as Yorkshire Water outlined their investment programme of replacing mains, reducing leaks and water treatment upgrades.

Their press release stated, ‘Average household water bills in Yorkshire are set to increase by 5.6% in April – around £2.80 per month – to help fund an £8.3bn investment programme, which will improve customer service and environmental outcomes across the region.’

They outlined that the regulator Ofwat had agreed to these increases for all water companies to raise bills yet again, in order to pay for upgrades after years of under investment from the water companies themselves- almost blaming Ofwat for the rises.

‘The increase, which was agreed by Ofwat in December 2024, sits just above inflation and will enable Yorkshire Water to continue delivering a wide range of infrastructure projects, totalling £1.1bn between April 2026 and April 2027, including:

–Progressing a £38m plan for reducing leakage across the region

-Replacing 353km of mains throughout Yorkshire, to reduce bursts and instances of water supply disruptions

-Exchanging a further 350,000 smart meters to help customers save water and reduce their bills.’

Matt Pinder, customer director at Yorkshire Water, said: “This is our largest ever investment package – designed to drive significant progress in areas we know are important to our customers. We’ve already delivered a huge number of infrastructure projects – over 200 in 2025 – and it’s important that we keep that momentum going over the next year, and beyond.

“The money we collect from customer bills, alongside shareholder investment and borrowing, will be spent on a wide variety of improvements across the region – from improvements to storm overflows to mains replacements and bringing in new water resources – alongside delivering a better service for our customers.”

He added: “Of course, we know that bill rises will be difficult for some of our customers. Over the five years, we’ll be providing £375m in financial support to 345,000 customers through a range of different schemes – I would encourage anyone who is struggling financially to contact us to discuss the options available to them.”

Why are customers paying to clean up the water industry?

Campaigners however decried the water industry’s claims that, ‘By 2030 £104 billion will be invested in the UK’s water networks.’ Fervent water campaigner, Feargal Sharkey challenged where the ‘investment’ was coming from, saying, ‘not a single bloody penny of any of it is coming from water company shareholders- it’s all coming directly out of bill payers pockets.’ He also highlighted the dangers of companies using the tactic of ‘big numbers’ to make their promises sound more convincing, while ignoring financial truths, when he pointed out that ‘£22 BILLION of that instantly evaporates in interest payments, commissions and other financial changes.’

Sharkey also listed the deficiencies within the water industry to make the point that they are operating with very little restrictions and that financial penalties do not act as a disincentive to clean up their act.

‘Water companies are currently £82.7 billion in debt, have paid themselves £85 billion in dividends, leak over a trillion of litres of water per year, dump sewage for almost 4 million hours per year, have been convicted of over 1,200 criminal acts since 1989 and an average of 35% of your bill goes on nothing but paying more interest and yet more dividends.

And not a single company has ever lost their operating licence.’

‘Bonuses’ continue

‘The Guardian’ recently reported that the water industry appeared to be circumventing the ban on bonus payments to bosses of the water companies by ‘labelling payments differently or paying bosses through linked companies.’

Frankly, at this stage, the water companies bosses and parent companies, must be laughing at the ineptitude of regulators and the government to hold them to account. The perception is that they are aware of the rising pressure for re-nationalisation of water and that they continue with business as usual, for as long as they are able to do so.

Come April, the public will all dutifully pay the rise in payments to the water industry, without real expectation of any improvements to the system. Sewage will still run rampant in our waterways, unchecked and unpunished. It is worth remembering that this rise in annual payments will happen at approximately the same time as the annual data on sewage pollution will be published. In Yorkshire in 2024, there were 450,398 sewage spills, with these spills lasting for 3.6 millions hours.

What is the number of sewage spills needed for the government to rein in this runaway industry?

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.