‘Climate change- and the energy, materials and food systems that drive it- is a massive but solvable problem.’

It is not often that we find a climate book that is openly honest, factual and optimistic about where we are in ‘one of the biggest challenges that humanity faces’. Ritchie structures this book into a question- answer format which makes the writing accessible, while at the same time, objective and factual. Her 50 questions are divided into 10 sections covering issues ranging from food, carbon removal, heating, electric cars, renewable energy and more. Every section has clear action points which are necessary to bring about the change that is needed. Her objective, data based clarity approach makes her writing compelling and her arguments convincing. She argues that ‘We are not only capable of solving climate change but also poised to create a better future for ourselves in the process. To do that, we first need to understand that it’s possible.’

Ritchie repeats that aiming for ‘perfect solutionism’ is a pathway doomed to failure. She argues, like many others, that we should not ‘let perfect be the enemy of good. ‘Another problem is that we seem to be stuck in something I call ‘perfect solutionism’. People seem to expect solutions to climate change that have no downsides…Unfortunately, perfect climate solutions don’t exist.’ She challenges what this search for a ‘perfect solution’ actually means: ‘We also need to recognise where a search for perfection will leave us: in a much hotter world, still hooked on fossil fuels, with millions still dying from air pollution.’

‘It won’t be straightforward, but it will be worth it.’

Ritchie begins by tackling some of the oft-repeated questions that seek to delay climate action. Some of these will now be summarised here, owing to the quantity of times we have seen these arguments. ‘Isn’t it too late? Aren’t we headed for a 5 or 6℃ warmer world?’

Ritchie tackles this question head on and deals with it by highlighting how much progress we have made from the early scenarios that suggested these higher global temperatures. She urges honesty in these discussions, in order that the public do not lose trust in the messages from climate scientists. Her succinct answer is that, ‘Every tenth of a degree matters. There’s no point at which it’s too late to limit warming and reduce damage from climate change.’

Attention is then turned to the issues of polarisation, or apparent political divides and support for climate action. Ritchie argues that the data indicates that ‘more people care about climate change than you think’ and that views on this are skewed by the preferred media that is consumed. She points to survey findings which indicate that the public welcome climate policy action. ‘A survey of 59,000 people across 63 countries found that 86% thought that humans were causing climate change and that it was a serious threat to humanity.’ Ritchie urges that talking to real people about climate issues and actions, such as installing solar panels or choosing to drive an electric car, can really make a local difference. When communities work together and people talk to each other, solutions can be found which then drive further innovation. ‘Systemic change is driven by culture and public sentiment, and how we all think and talk about climate solutions shapes that culture.’

Why should my country act when others are not acting?

Ritchie also explores the ‘1%’ argument when she poses the question, ‘My country only emits 1% of the world’s emissions; surely it’s too small to make a difference?’ She highlights two factors here when this is used as an excuse not to act; one, that ‘the world’s ‘small emitters’ make up more than one-third of the world’s emissions, enough to significantly turn the dial’ and secondly the moral argument of understanding the importance of historical emissions and not just emissions now. ‘There is also a strong moral argument for why countries like the UK should care, even if their emissions today are not a big piece of the pie. The UK emits just 0.9% of emissions, but if we add up all its historical emissions, it accounts for 4.5%.’ Countries like the USA historically have emitted around 24%, but the spotlight is rarely focused on them, but rather the climate scapegoat of China.

Ritchie does focus on China and answers the question, ‘Aren’t our efforts pointless if China’s emissions keep growing?’

She acknowledges China’s position now, but also highlights its climate leadership position, when she argues that the data demonstrates that, ‘China is the world’s largest emitter but it’s rolling out renewables and electric vehicles at breakneck speed.

China is rolling out solar and wind at a staggering rate. In a single year, it builds enough solar and wind to power the entire UK. In 2023, it installed more solar power than the US had in its entire history.’

She makes the point that, ‘[r]elying on others is a geopolitical liability’, one which was demonstrated only too well in the UK, when the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was felt in electricity prices. Her point is that solar and wind energy are free in every country, although some countries may make decisions on their energy needs depending on their geography and local conditions.

The future is there, waiting for us to take it. Or, rather, build it.

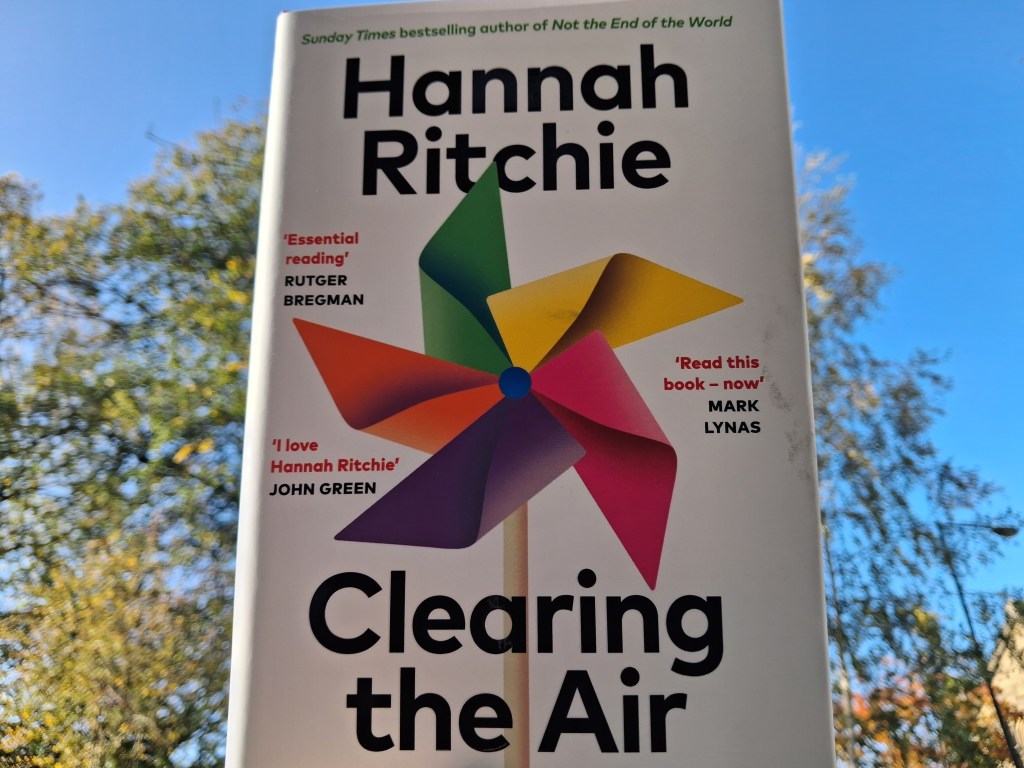

‘Clearing the Air’ continues in this analytical approach, outlining the facts around electric cars, the energy needs from the food industry, heating and cooling and nuclear power- the ‘big topics’ of climate discussions and policy. Throughout, Ritchie stresses what the data indicates, which heightens the optimistic possibility of what can be achieved.

‘Getting our emissions to zero- while providing a good life for billions of people- is one of the biggest challenges that humanity faces. It’s possible to do it, and there are very few technical constraints in our way, but that doesn’t mean it’ll be easy.’

Ritchie finally urges us to understand and appreciate that a mindset shift will help enormously. We accept that society has changed in the past- oftentimes very quickly, but oddly, we find it difficult to project this understanding into future events.

‘We accept that changes have happened in the past but are sceptical that tomorrow, next year or the next decade will be much different.’

It can be difficult, when living in a transitional moment, to recognise that change is happening and that attitudes are shifting. But looking back to how much progress we have made to reduce emissions and to negate high emission pathways, demonstrates that significant progress has been made.

The journey has already started.

Where it ends, is up to us.